How to Learn in this Class¶

Over the years, we’ve found that one of the things that CS 121 students struggle with most is not necessarily the content of the class, but the manner in which one learns how to program or, more concretely, the manner in which one becomes a better programmer. Most notably, when a CS 121 student keeps coming up with wrong solutions, or has a hard time figuring out a bug, or keeps failing the tests in an assignment, two things tend to happen:

They do what has worked for them in some other classes: review the textbook, ask for additional readings, re-read your solutions to the homeworks and the grader’s comments, etc.

They feel bad because their code keeps failing, and get into the mindset that “my code fails, therefore I must be a failure too”.

Let’s start with #1. While doing those things may help a bit, they are not a great strategy to do well in this class or, in general, to become a better programmer.

So, how do you become a better programmer?

By stepping on the rakes.

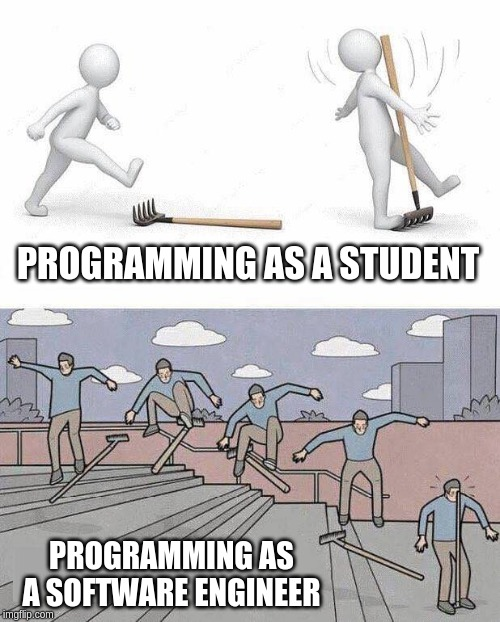

Wait, what? Let’s explain what we mean with the following diagram:

While programming (and computational problem solving) are rooted in many foundational concepts in Computer Science that you need to study and understand to be a good programmer, programming is ultimately a skill and, like many skills, you get better at it the more you practice. Unfortunately, while there are definitely a number of best practices that you can learn about in class (and in countless books), there are no Golden Rules of Programming such that, as long as you memorize and follow those rules, your programs will be guaranteed to always be perfect.

One of the best way to hone your programming skills is to write code, and then have more experienced programmers review it and tell you how to improve it (or, in a class like this, getting your code graded). More often than not, you’ll start by writing some pretty awful code, and that is ok. That is part of the learning process. You have to write bad code to understand why it is bad, and how to avoid making that same mistake in the future.

In other words, you have to step on the rake to know to avoid that particular rake in the future. Seasoned programmers are not naturally talented or “born to program”: they’ve just stepped on so many rakes that they’ve gotten really good at avoiding them (but we still step on them now and then… and how!) Or, as a (probably apocryphal) art professor used to tell art school students: “You all have 10,000 bad drawings in you, and our goal is to get through those as quickly as we can”. Similarly, you all have a lot of bad lines of code in you, and we need to get them out of your system by making you write tons of code this quarter.

Now, this leads us to point #2 above. For this learning process to be effective, you have to open yourself to doing a bad job so you can learn from it or, to quote Adam Savage from Mythbusters, you have to accept that…

Many people (including many students) are conditioned to interpret failure as an unequivocally bad thing. If we assign you your first programming exercises, and you do poorly in them, you will likely see this as a negative: “I got a bad grade, therefore there is something wrong with me and/or I will never be good at this”. While we don’t deny that getting a poor score in an assignment can be unpleasant, it does not mean you are a failure or that there is something wrong with you. Yes, you didn’t get everything right but, then again, it is very rare for beginner programmers to get everything right on their first try.

You may also feel frustrated when we point out a mistake in your code that we didn’t explicitly forbade or told you to avoid before you submitted an assignment. Unfortunately, it is not feasible for us to communicate in advance every single possible way in which a piece of code could turn out to be wrong (again, because there are no Golden Rules of Programming that can be learned or applied in that way). The feedback you receive in an assignment or an exam are our way of telling you that we spotted something you should avoid doing in the future.

So, don’t be discouraged if it feels like you keep getting things wrong at first. Take that failure constructively, and learn as much as you can from it. Or, in other words, if you step on a bunch of rakes, don’t get angry or frustrated that you didn’t see the rake (or that someone didn’t yell “Hey, there’s a rake there!”). Instead, focus on not stepping on those rakes again!